Editor’s note: This is the last of a series of articles in advance of the Shelby County Historical Society’s Week of Valor, which begins Sunday, Aug. 30, and includes the return to Sidney of the Vietnam Memorial replica wall and a Field of Valor featuring American flags in Custenborder Park. Flags for the Field of Valor can be purchased by calling 498-1653. The project commemorates 2015 as the anniversary of the beginning or end of several U.S. armed conflicts. This series has included stories about most of America’s wars. Today, a Vietnam War veteran remembers his service.

SIDNEY — Ask U.S. Army veteran Cecil Steele, of Sidney, about his service in Vietnam during the war and he says something surprising: “I was never wounded. I never got any medals. I was lucky.”

He may never have been hurt, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t in danger. A door gunner in a Huey helicopter, he was routinely shot at.

“Every time we came back, you’d have to check the choppers for how many holes we had. You always got hit,” he said.

Steele was working at Emerson Electric when he was drafted in 1967. He was “in country” in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969, attached to the 13th Aviation Battalion. After boot camp at Fort Benning, Georgia, he was sent to Fort Rucker, Alabama, for training in fire and rescue operations. His orders were confusing, however, which turned out to be a recurring problem.

Steele was told he couldn’t go through basic training graduation exercises because he had to get a plane to Fort Rucker right away.

“‘Your school starts Monday,’ they said,” he recounted. As it turned out, his training wasn’t going to start for another month.

“I was on KP for 30 days,” he said. “I swore I’d never wash another dish.”

From there, he was sent to Vietnam with orders clearly stating that he was to report to a base in Soc Trang. But the “brass” in country had other ideas.

“That experience was something else,” Steele said of his entry into the war. “It was a total mess-up.” He was sent to Saigon.

“I got to Saigon. They said, ‘You don’t belong here. You should go down to Dak To.’ I got there. They said I’m supposed to go to the Mekong Delta. They said I have to go to Can To.”

Steele was in Can To for two weeks, guarding prisoners of war, when he was told he had to hurry to catch a flight to Soc Trang.

“They finally got me where I was supposed to go,” he said. “I was part of what they called ‘the big buildup.’”

As a fire and rescue crew chief, Steele and his team were responsible for getting people and equipment to safety when choppers went down.

“I wasn’t there too long and a chopper came in and it was shot up,” he said. “There was a village there. It crashed into the village. It killed a (Vietnamese mother) holding a baby. We saved the baby. It was devastating to me.”

One day, he and the seven other recruits who were the most recent arrivals at the base were told to line up.

“They were short of door gunners,” Steele said. Every other man in the line was tapped for that duty, and Steele was one of them.

“It wasn’t a full-time thing. We’d go out twice or three times a week,” he said. The chopper crews provided fire cover for “rat patrols” on the river — U.S. Navy crews who were searching for the enemy .

“When Navy boats came under fire, we’d cover for them,” he said. He also transported prisoners and American VIPs.

“The only thing I didn’t like was when VIPs came in,” he said. “You’d have to cater to them. I didn’t think they should have been there to begin with.”

It wasn’t just fellow American servicemen he worked with. Some of the people on his fire and rescue crew were Vietnamese. Steele learned enough of their language to get by, but he didn’t need to learn a lot.

“The Vietnamese on my crew spoke pretty good English,” he said. “When I was there, I liked the people. But after a while, I didn’t like any of it. I hated it. But it wasn’t their fault (that) I was there. The crew I had were good people. I’ve often wondered about them, if they made it when the North took over.”

Steele considered making a career of the Army, but when he was told that he’d have to spend another year in Vietnam to do so, he declined. In all, he was there for 16 months, longer than a usual tour of duty in the war zone. But that was because the end of his service was as mixed up as the beginning.

“I was there a year and they said, ‘You’re going home,’” Steele remembered. “I packed my bags and was ready. I was supposed to leave within a week.” But it was another four months before he actually shipped out.

Two of Steele’s most vivid memories of those days in Vietnam are the smell of the country and the temperature.

“The heat was something else,” he said.

And then, he was home.

“It was hard. I had a rough time for a while. I had a hard time sleeping. I still sometimes have a hard time,” he added.

He returned to work at Emerson as a job setter and then a CMM operator and retired in 2007 after 34 years there. Married to Shirley, he has two daughters, Jackie Steele, of Dallas, Texas, and Amanda Brooks, of Sidney; a stepdaughter, Terrie Greve, of Florida; and three grandchildren.

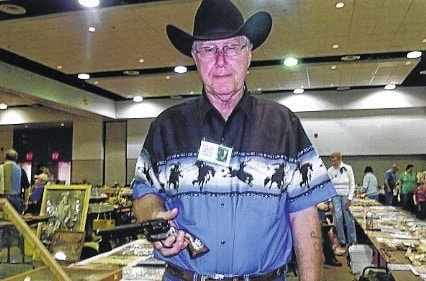

He and a friend now buy and sell cowboy memorabilia at auctions and antique fairs. A Roy Rogers fan, he’s also a frequent volunteer for the Shelby County Historical Society.