Editor’s note: in conjunction with the 200th celebration of the establishment of Shelby County, the Sidney Daily News will be publishing a year long series about the county’s history.

There is no record of who the first European was to lay eyes on this land. Perhaps it was a solitary fur trader from France who first visited the Miami River Valley. The answer is lost forever in the mists of time, like a fog that veils the land on a spring morning.

What we do know is that by the early 1700s, France considered Ohio to be her land. England was busy establishing colonies east of the Appalachian Mountains but would soon cast longing glances to the west and send her own fur traders here to do business with the Indians of the Ohio Valley.

It would not be long before the struggle between these two European powers would spill into the land that is today Ohio. France, with her strength in Canada, and England, from her eastern toehold, would both take economic, political, and military action to win control of this land.

In 1747, a group of Twightwee (Miami) Indians, lead by Memeska, came to the confluence of the Great Miami River and Loramie Creek. Memeska brought his followers to this place called Pickawillany to be closer to his new friends, the English.

Memeska was coming to Ohio from Kekionga (Fort Wayne) to put distance between himself and his former French allies, who dominated the Great Lakes region. For many years, the French had been the only game in town in the Great Lakes fur trade. However, growing dissatisfaction with high prices, poor quality, and short supplies of French goods led Memeska and others to look to the English as a more reliable source of trade goods.

It was not long after the move to Pickawillany that a treaty of friendship between Memeska’s Twightwee and the English was forged at Lancaster, Pennsylvania. On the heels of that agreement came English traders, employed by Pennsylvanian George Croghan, who established a trading station next to the village of Pickawillany.

Word spread quickly that English goods were now available at Pickawillany. This brought rapid growth to the village. Indians, not only from the Ohio country, but also the Great Lakes region and westward, came to the village to do business.

In 1750, Christopher Gist, an agent for Virginia’s Ohio Land Company, visited Pickawillany. Gist estimated that in 1750, the village numbered approximately 1,200 individuals.

The trading activity was not lost on the French authorities. They viewed Memeska (who they called La Demoiselle) as a serious threat to their control of the Indian fur trade. Almost from the moment Pickawillany was established, the French had begun planning how best to remove this thorn from their side.

In 1749, French officials in Canada sent Pierre Joseph Celoron and a force of 265 men into the Ohio Valley to reinforce French authority and strengthen their claim to the Ohio country. The group stopped at key points to conduct ceremonies in which they buried lead plates in the ground at the mouths of rivers draining into the Ohio claiming the land for the King of France.

At best, their expedition received a cool reception from the Ohio Indians. As a result, each ceremony Celoron conducted was of brief duration before he quickly moved on. Celoron was keenly aware that even as he was reclaiming the land for his king, English influence was growing daily.

On September 13, 1749, after an arduous journey up the Great Miami River, Celoron and his men arrived at Pickawillany. As he traveled upstream, he held out hope of convincing Memeska to return to the French fold. Just as Celoron was approaching the village, several English traders packed their trade horses and left. Celoron found only two English traders in the village when he arrived. They were ordered to leave, and they promptly did.

While Celoron was able to overawe the traders, Memeska was another story. Pickawillany’s population and influence was growing, and Celoron knew he was not strong enough to force the Indian’s removal to Kekionga.

When they met in council, Memeska did promise Celoron “none but good answers”. The Frenchman believed Memeska’s promises to return to the old homeland in the spring to be merely a stalling tactic. Celoron ended his council with Memeska with this warning:

“Be faithful to your promise. You have assured him of this, because he is much stronger than you, and if you be wanting it, fear the resentment of a father, who has only too much reason to be angry with you, and has offered you the means of regaining his favor.”

Celoron and his men left, knowing that they had failed to accomplish their mission. It was shortly after Celoron’s exit that George Croghan and his Pennsylvania traders arrived at Pickawillany to officially establish an English trading post.

Soon a brisk trade business was flourishing near Memeska’s village. Because of his friendship with the English traders, Memeska was known as ‘Old Briton’ to his English allies.

Through 1750 and 1751, Pickawillany continued to grow as both a village and a trading center. Traders George Croghan, Andrew Montour, and Christopher Gist were all present at one time or another at Pickawillany and brought additional traders. They also helped Memeska improve and strengthen his village.

Early in 1751, Celoron was ordered to again visit Pickawillany and employ force if necessary to take Memeska back to Kekionga. However, being unable to raise the needed men, he did not leave the security of the French headquarters in Detroit.

In the autumn of 1751, a small French force did advance on Pickawillany, only to find most of its residents away on the fall hunt. Even so, the French were not strong enough to mount an attack. They did seize some English traders and kill a Twightwee man and woman.

French officials saw their position in Ohio rapidly deteriorating and determined to take the necessary steps to stop this erosion of their control. In March of 1752, they put in motion plans to organize a stronger raid on Memeska and his village.

On June 21, 1752, a force of about 250 Ottawa Indians and French militia, led by Charles Langlade, attacked Pickawillany. Many of the Twightwee men were hunting, leaving the village occupied primarily by women, children and a few older men. Also present were Memeska and his family. In addition, several English traders were present and working at their trading station.

The attack was so sudden that many of the women were captured as they worked in the surrounding cornfields. Others fled to the village stockade in hopes of protecting themselves. Three traders were unable to flee and were forced to seek protection in one of the traders’ cabins near the stockade.

These traders quickly surrendered to the invaders without firing a single shot in their own defense. To save themselves, they told Langlade how few defenders were inside the Twightwee stockade.

A siege of the stockade was laid down, and the defenders were told that if they would but surrender the traders and their goods, the attackers would leave Pickawillany. Inside the stockade, with several defenders wounded and water supplies exhausted, the defenders agreed to the terms they had been offered.

Five of the seven traders in the stockade were surrendered. Gunsmith Thomas Burney and trader Andrew McBryer were hidden and later escaped to carry the news of the attack to the English at Lower Shawnee Town (Portsmouth).

One of the five surrendered traders had been wounded. As soon as he was seized, he was stabbed to death, scalped, and his heart ripped from his chest and eaten.

Memeska faced a similar fate. The French saw him as the cause of most of their problems in Ohio and the primary agent for the English. Before his remaining followers, including his wife and son, he, too, was killed, boiled, and his body eaten.

The remaining traders and their captured goods were gathered and marched to Detroit. With this defeat, the Pickawillany thorn was at last removed from the side of the French.

The surviving Twightwee moved back to the protection of Kekionga. Pickawillany was not occupied as a village site again.

After the removal of the Twightwee, the Shawnee eventually moved into the Miami River Valley in the late 1750s and began establishing a few villages in the region.

Editor’s Note: The inhabitants of Pickawillany certainly hunted and fished throughout Shelby County and beyond. Today, the former site of Pickawillany is located on property owned by the State of Ohio, a part of the property controlled by Ohio History Connection and operated as the Johnston Farm & Indian Agency. The last excavations there were conducted over three summers earlier in this decade. Much of what was found is on display at the museum at the Johnston Farm.

Photo captions:

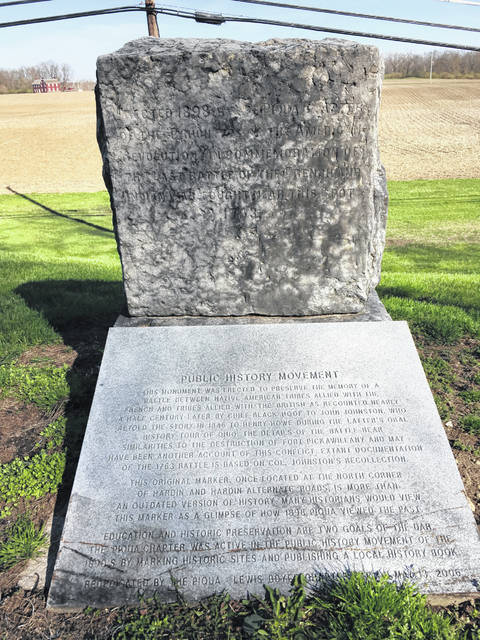

The first monument commemorating the Battle of Pickawillany is today located just off State Route 66 on the Hardin Pike. It reads: “Erected in 1898 by the Piqua Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution commemorating the last battle of the French and Indian War fought near this spot in 1753.” Colonel John Johnston’s home can be seen in the background.

A second monument, also placed by the Piqua Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, reads: “Pickawillany located one mile northeast of the memorial headquarters of the Miami tribes, (the) first English settlement and the most important trading post in the west 1748. Destroyed by the French 1752.”

As part of Ohio’s Bicentennial, the Ohio Bicentennial Commission, the Ohio Historical Society and the Marietta Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution teemed to erect still a third marker. This one reads: “In the mid-1700’s, France found its influence waning among Midwestern tribes as it contested for Native American trade and military alliances with Great Britain. Shortly after Miami Chief Memeskia (also known as Old Britain or La Demoiselle) moved his village to Pickawillany. British traders were given permission to establish a small post in the village, which was deep in the territory claimed by France. When French demands to evacuate the post failed, Charles Langlade led a party of 250 Ottawa and Ojibwa warriors and French Canandians in a surprise attack on the Miami village on June 21, 1752. The trading post was destroyed. British traders were taken to Detroit as prisoners, and Memeskia was executed. Pickawillany was completely abandoned soon after. As a prelude to the French and Indian War, the Battle of Pickawillany fueled land claim and trading right conflicts between France and Britain.”